Terrorism is usually understood as the use or threat of violence to further a political cause. There is no universally agreed definition of terrorism making it a difficult object to quantify. For clarity, the Data Quality & Definitions sectionbelow carefully outlines the definition used in constructing the dataset presented here and compares it with the legal definition in the UK. While acts of terrorism across the globe have increased markedly in recent decades, in most parts of the world it continues to be a relatively rare event and is instead focused in particular countries or regions of instability.

Empirical View

Historical terrorism

Terrorism is not a 21st century phenomenon and has its roots in early resistance and political movements. The Sicarii were an early Jewish terrorist organisation founded in the first century AD with the goal of overthrowing the Romans in the Middle East. Judas of Galilee, leader of the Zealots and a key influence on the Sicarii, believed that the Jews should be ruled by God alone and that armed resistance was necessary.

Unlike the Zealots, the Sicarii targeted other Jews they believed to be collaborators or traitors to the cause. The tactics employed by the Sicarii were detailed by the historian Josephus around 50AD: “they would mingle with the crowd, carrying short daggers concealed under their clothing, with which they stabbed their enemies. Then when they fell, the murderers would join in the cries of indignation and, through this plausible behavior, avoided discovery.”1

There are many other key examples of terrorism throughout history before the modern terrorism of the 20th century. Guy Fawkes’ failed attempt at reinstating a Catholic monarch is an example of an early terrorist plot motivated by religion. Meanwhile, The Reign of Terror during the French Revolution is an example of state terrorism.

Modern terrorism after the second world war

The use of terrorism to further a political cause has accelerated in recent years. Modern terrorism largely came into being after the Second World War with the rise of nationalist movements in the old empires of the European powers. These early anti-colonial movements recognised the ability of terrorism to both generate publicity for the cause and influence global policy. Bruce Hoffman, director of the Centre of Security Studies at Georgetown University writes that, “The ability of these groups to mobilize sympathy and support outside the narrow confines of their actual “theaters of operation” thus taught a powerful lesson to similarly aggrieved peoples elsewhere, who now saw in terrorism an effective means of transforming hitherto local conflicts into international issues.”2 This development paved the way for international terrorism in the 1960s.

The following charts highlight the extent to which acts of terrorism are concentrated geographically in areas of conflict and instability. The first shows how deaths from terrorism has declined in recent years if we exclude deaths in Iraq and Afghanistan. While the global count of terrorist acts spiked in 2006, this was primarily driven by the insurgency in Iraq. The second chart is a time series count of terrorist incidents in a select group of countries.

Rate of deaths from terrorism worldwide, 1970-2007 (except Afghanistan since 2001 and Iraq since 2003) – Pinker (2011)3

Terrorism after 9/11

The attacks of 11 September 2001, known as 9/11, marked a turning point in world history and the beginning of the ‘War on Terror’. The attacks are estimated to have killed 3000 people making it the deadliest terrorist incident in human history. The subsequent War on Terror led to the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003. The following table summarises the concentration of terrorist attacks pre- and post-9/11. It reveals that terrorism pre-9/11 was concentrated in Latin America and Asia, but shifted to the Middle East post-9/11–Peru, Chile and El Salvador completely disappear from the top 10. More than a quarter of all terrorist attacks between 9/11 and 2008 took place in Iraq.

Top 10 most attacked countries and territories, 1970 to September 11, 2001 and September 11, 2001 to 2008 – Peace and Conflict 20124

| 1970 to 9/10/2001 | 9/11/2001 to 2008 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Country | % of All Attacks | Country | % of All Attacks |

| 1 | Colombia | 8.88 | Iraq** | 25.77 |

| 2 | Peru* | 8.35 | India | 9.48 |

| 3 | El Salvador* | 7.38 | Afghanistan** | 9.03 |

| 4 | Northern Ireland | 5.13 | Pakistan | 7.63 |

| 5 | India | 4.61 | Thailand** | 5.84 |

| 6 | Spain | 4.14 | Philippines | 3.85 |

| 7 | Turkey | 3.49 | Russia** | 3.65 |

| 8 | Chile* | 3.15 | Colombia | 3.22 |

| 9 | SriLanka | 3.03 | Israel | 2.89 |

| 10 | Phil ppines | 2.96 | Nepal** | 2.55 |

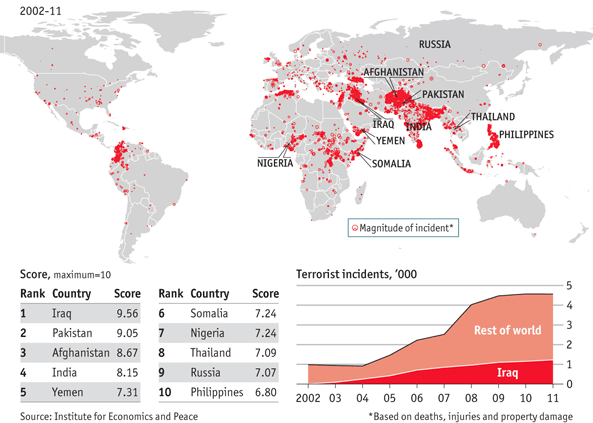

The shifting concentration of global terrorist activity can be seen in the following map. Terrorism post-9/11 has been concentrated in predominantly muslim countries as a result of radical Islamic ideologies and sectarian violence.

Data and world map on global terrorism, 2002-2011 – The Economist5

Airline hijackings and international terrorism

The deadliest terrorist attacks in history, the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center, were the result of two plane hijackings. Yet aviation terrorism has a long history and its development marks the beginning of international terrorism. On 22 July 1968, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) hijacked Israeli El Al Flight 426 from London to Tel Aviv via Rome. They diverted the flight to Algiers where they held the Israeli hostages for several days while they negotiated the release of Arab prisoners in exchange for the hostages. Once the terms were agreed the hostages were released with no fatalities.

The success of this early hijacking made it an increasingly popular weapon of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO). In 1976 Zehdi Terzi, the first PLO representative to the United Nations, stated that the “first several hijackings aroused the consciousness of the world and awakened the media and world opinion much more–and more effectively–than 20 years of pleading at the United Nations.”

Terrorism in specific countries and regions

By default the following two charts show how terrorist incidents have evolved in Afghanistan and Iraq following the War on Terror. It is possible to change the countries displayed in the visualisation below.

While terrorism in the Middle East has spiked in recent years, there have been successes in combating terrorism elsewhere. One notable example is the ETA, the Basque separatist movement in Spain, which put down arms in 2011.

Terrorism in the Spanish Basque Country: Deaths attributed to ETA – The Economist (2010)6

The risk of terrorism in a broader perspective

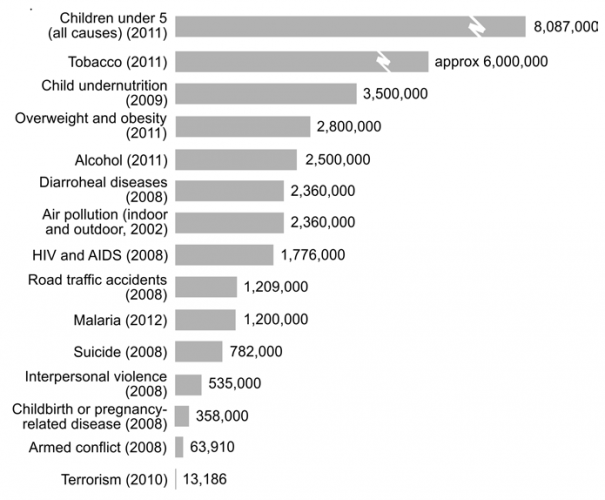

Despite the intense media focus on terrorist activity around the world, the numbers of people actually killed by terrorist attacks has remained low. Terrorism only killed 13,000 in 2010, a relatively low number when compared with other types of violent death, namely armed conflict and interpersonal violence.

Global death toll of different causes of death – Oxfam7

Correlates, Determinants & Consequences

Rational motives?

Martha Crenshaw, professor of Political Science at Stanford, argues that terrorist groups make calculated decisions to engage in terrorism, and moreover, that terrorism is a “political behavior resulting from the deliberate choice of a basically rational actor.”8In addition to this, she suggests “Terrorism is a logical choice … when the power ratio of government to challenger is high.”

Crenshaw breaks down the causes of terrorism into three layers:

- Situational factors: This can be subdivided into two parts; (1) conditions that allow the possibility of radicalisation and motivate feeling against the ‘enemy’, and (2) specific triggers (events) for action.

- Strategic aims:

- Long-run; political change, revolution, nationalists fighting an occupying force, minority separatist movements

- Short-run; recognition or attention to advertise their cause

- Disrupt and discredit the process of government

- Influence public attitudes; fear or sympathy

- Provoke a counter-reaction to legitimise their grievances

- Individual motivations: This is concerned with psychology and the character traits of terrorists; why do individuals turn to terrorism in the first place? does a ‘terrorist personality’ or ‘terrorist predisposition’ exist?

The war on terror

One major consequence of the rise of international terrorism, particularly Islamic extremist groups, has been the global War on Terror. The War on Terror, which began in 2001, has so far seen the full-scale invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as other operations in Yemen, Pakistan and Syria.

An important question is whether the global campaign against terrorism, known as the War on Terror, has made us any safer. Many commentators argue that the War on Terror has had the perverse effect of making us less safe, with some going as far as claiming the War on Terror is the leading cause of terrorism. Richard Clarke, a counter-terrorism expert that worked in the US National Security Council between 1992–2003, was highly critical of the Bush administration’s counter-terrorism strategy and the decision to invade Iraq.9 Clarke writes: “Far from addressing the popular appeal of the enemy that attacked us, Bush handed that enemy precisely what it wanted and needed, proof that America was at war with Islam, that we were the new Crusaders come to occupy Muslim land.”

The internet

The internet has become a central tool for terrorists, largely replacing print and other physical media. It has allowed terrorist organisations to costlessly communicate their message and aims to the world, allowing them to recruit new members, coordinate global attacks and better evade surveillance. The terrorist group known as the Islamic State (also, ISIS and ISIL) are arguably the first to harness the power of the internet and social media. Their well-organised online propaganda campaign has seen them recruit thousands of foreign fighters.

The increasing use of the internet was noted by Bruce Hoffman in Inside terrorism as early as 2006. He argues that “terrorists are now able to bypass traditional print and broadcast media via the Internet, through inexpensive but professionally produced and edited videotapes, and even with their own dedicated 24/7 television and radio news stations. The consequences of these developments [are] far-reaching as they are still poorly understood, having already transformed the ability of terrorists to communicate without censorship or other hindrance and thereby attract new sources of recruits, funding, and support that governments have found difficult, if not impossible, to counter.”10

Does terrorism work?

Measuring the effectiveness of terrorism requires us to have both a well defined set of objectives for a given terrorist organisation as well as a definite way to determine success and failure. Consider the example of 9/11 and whether Al-Qaeda achieved its objectives: If the objective was to destroy America, then it clearly failed. Yet if goal was to intimidate America and publicise the cause, it may be considered a success.

With respect to the question of effectiveness, there are two opposing views in the literature. The first posits that terrorists are able to influence policy and public opinion and that terrorism is increasing worldwide simply because it is effective. The second view argues that terrorists hardly ever achieve their main objectives and that terrorist groups tend to be unstable and disintegrate over time.

Robert Pape, professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago, is a major proponent of the view that terrorism can be effective and his research focusses on suicide terrorism. Pape finds that suicide attacks targeted at democracies tend to be more effective at influencing policy.11 Recent research by Eric Gould and Esteban Klor support this view; they find that terrorist attacks in the Arab-Israeli conflict influence public opinion and “cause Israelis to be more willing to grant territorial concessions to the Palestinians.”12 Jakana Thomas, by focussing on other markers of success, finds that in African conflicts between 1989-2010 “rebel groups are both more likely to be granted the opportunity to participate in negotiations and offered more concessions when they execute a greater number of terror attacks during civil wars.”13

Max Abrahms argues that terrorism never succeeds. Abrahms analysed 28 groups designated as terrorist organisations by the US State Department in 2001.14 He finds that the groups only achieved 7 percent of their 42 policy objectives. Moreover, Abrahms suggests that his findings “challenge the dominant scholarly opinion that terrorism is strategically rational behavior.” Further support for the idea that terrorism never succeeds comes from Audrey Cronin’s research on the collapse of terrorist groups.15 Cronin also finds that terrorist groups fail to achieve their objectives and that these groups only last between 5-9 years on average.

Data Quality & Definitions

Data quality

Ivan S. Sheehan has written on the importance of data quality in terrorism research and highlights several key issues that researchers must be aware of when using these datasets.16 Firstly, the issue of definition becomes important. Consider the example of Palestinian terrorist attacks in Israel; should these be coded as international or domestic terrorist attacks. Furthermore, can a state-entity engage in terrorist activity? Issues such as this lead to large discrepancies between commonly used datasets. The following chart shows just how large these discrepancies are between the ITERATE and RAND datasets.

ITERATE vs. RAND MIPT: quarterly number of transnational terrorist incidents, 1993 – 2004 – Sheehan (2012)17

Another issue is that many of these databases were developed in the intelligence and defence communities before being used by researchers. This has meant that they often lag behind the normal data standards of academic datasets, however this is changing. Sheehan also suggests that retrospective data collection can yield underestimates since “not all sources that are available in real time are still available or accessible years later.”

RAND Database of Worldwide Terrorism Incidents and Bruce Hoffman

The data visualisations in this page are generated using the RAND Database of Worldwide Terrorism Incidents, and so it is important to understand the definition used in their construction. The RAND database uses the following definition of terrorism:

Terrorism is defined by the nature of the act, not by the identity of the perpetrators or the nature of the cause; key elements include:

- Violence or the threat of violence

- Calculated to create fear and alarm

- Intended to coerce certain actions

- Motive must include a political objective

- Generally directed against civilian targets

- Can be a group or an individual

Their definition is closed tied to Bruce Hoffman’s definition:18

We may therefore now attempt to define terrorism as the deliberate creation and exploitation of fear through violence or the threat of violence in the pursuit of political change. All terrorist acts involve violence or the threat of violence. Terrorism is specifically designed to have far-reaching psychological effects beyond the immediate victim(s) or object of the terrorist attack. It is meant to instill fear within, and thereby intimidate, a wider “target audience” that might include a rival ethnic or religious group,an entire country, a national government or political party, or public opinion in general. Terrorism is designed to create power where there is none or to consolidate power where there is very little. Through the publicity generated by their violence, terrorists seek to obtain the leverage, influence, and power they otherwise lack to effect political change on either a local or an international scale.

Legal definition

One important point of departure in many legal definitions of terrorism is computer hacking. The ‘interference with or disruption to an electric system’ is explicitly stated in UK terrorism law; this does not fit into the definitions above which centre on violence. The UK the Terrorism Act 2000 defines terrorism as:

The use or threat of action designed to influence the government or an international governmental organisation or to intimidate the public, or a section of the public; made for the purposes of advancing a political, religious, racial or ideological cause; and it involves or causes:

- serious violence against a person;

- serious damage to a property;

- a threat to a person’s life;

- a serious risk to the health and safety of the public; or

- serious interference with or disruption to an electronic system.

Data Sources

RAND Database of Worldwide Terrorism Incidents

- Data: Date and location of the attack, weapons used, injuries, fatalities and description

- Geographical coverage: Global by country

- Time span: 1968-2009

- Available at: http://www.rand.org/nsrd/projects/terrorism-incidents.html

Global Terrorism Database

- Data: 140,000 terrorist attacks with 45-120 variables for each

- Geographical coverage: Global by country

- Time span: 1970-2014

- Available at: http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/

Integrated Network for Societal Conflict Research (INSCR)

- Data: High casualty terrorist bombings

- Geographical coverage: Global by country

- Time span: 1989-2014

- Available at: http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html

International Terrorism: Attributes of Terrorist Events (ITERATE)

- Data: International terrorist incidents

- Geographical coverage: Global by country

- Time span: 1978-2011

- Available at: http://library.duke.edu/data/collections/iterate, restricted to Duke University members