(CNN)Islam and Ahmed met online, looking for their “happily ever after” through a Muslim dating site.

Bride of ISIS: From ‘happily ever after’ to hell

But instead of bringing love and contentment, their marriage left Islam trapped in a living nightmare.

Fast forward four years — and three husbands – and she and her two small children are caught in limbo in northern Syria.

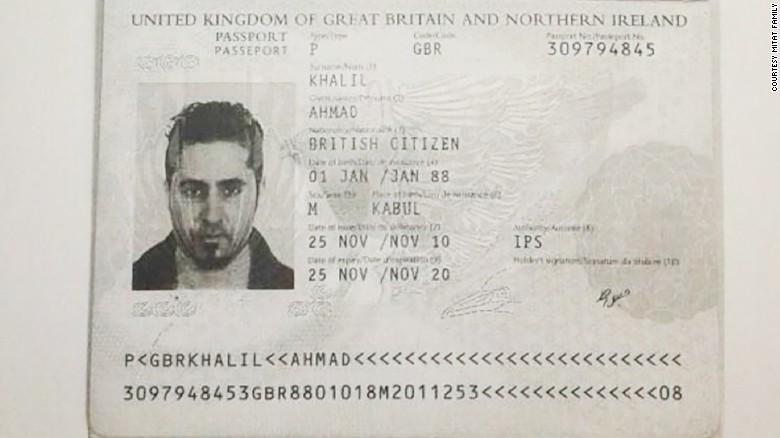

Islam Mitat is from Morocco; Ahmed Khalil was originally from Kabul in Afghanistan, but had moved to the UK and become a British citizen by the time they met on Muslima.com.

Mitat dreamed of a career as a fashion designer, and saw a British husband as a way out of her drab existence in the Moroccan town of Oujda, near the Algerian border.

Months after their first online encounter, Khalil traveled to Morocco with a woman he said was his sister. He met Mitat’s family, and proposed marriage, showing them bank statements to prove his intentions were serious.

“He was a normal person,” Mitat recalls, though she says he did make her swap her regular choice of clothing — tight jeans and t-shirts – for long dresses.

After they were married, the couple traveled to Dubai, and from there to Jalalabad in Afghanistan to meet Ahmed’s family.

Mitat says she only stayed in Afghanistan for a month, because of the security situation there, before returning home to Morocco.

Khalil went back to Dubai, but shortly afterward he called her with news. “He told me had a job in Turkey,” she says, “and we’re going to go for a holiday too, me and him.”

The “holiday” got off to a strange start. Instead of heading to a resort or a hotel, the couple flew to Gaziantep, on southern Turkey’s border with Syria.

A man who spoke only Turkish drove them to a house full of men, women and children. The women and children were in one room, the men in another, Mitat says.

She was confused, and asked the other women where they were going. “We’re going hijra,” they explained. To Syria.

Hijra was the journey of the Prophet Muhammad and his followers, the fledgling Muslim community, from Mecca to Medina in 622 to escape persecution. In a modern context, it signifies escape from the tyranny of the enemies of Islam to the realm of the faithful.

“When we were in Dubai he told me, ‘I have for you a surprise, but I will give it to you in Turkey.’ This is the surprise: to go in Syria,” she says.

When she objected, Khalil’s response was blunt.

“You are my wife and you have to obey me,” she says he told her.

Mitat says she wanted to tell Turkish border officials about her predicament, but says that as she and the others approached the Syrian border, the guards opened fire so they ran into Syria. When asked about the incident on the border, a Turkish police spokesman said he could not share information about individual cases.

Once inside the country, they headed to the nearby town of Jarablus, to a guesthouse for “muhajarin” — those who were making hijra to the so-called caliphate – like them.

Mitat says the place was packed with people from “everywhere” — the UK, Canada, France, Belgium, Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria and Saudi Arabia.

No sooner had they arrived, than Khalil was sent off for a month of military training, leaving Mitat, who was now pregnant, behind.

Once he’d been trained, ISIS sent Khalil to fight. He was killed on his first day, in the battle of Kobani.

After his death, Mitat says she was terrified and didn’t know what to do; banned from talking to ordinary Syrians, she was forced to stay within the muhajirin community.

She moved in with her husband’s brother and his family, who had also traveled to Syria, but when her brother-in-law was killed too, ISIS moved her into a guesthouse, where she stayed until her son, Abdullah, was born.

As Kurdish fighters closed in, ISIS told Mitat she had to marry again and get out of the area to safety, so she wed a friend of her first husband, a man known as Abu Talha Al-Almani (his name means “the German”).

He took her to Manbij, northeast of Aleppo, before moving again, this time to Raqqa as Kurdish forces closed in.

A month after they got there, Mitat says she divorced Abu Talha because he wouldn’t let her leave the house.

She says fear played a major role in her decision not to leave immediately. Islam says she was told that other people who tried to leave had their children taken away, or were forced into weeks of intense Islamic studies.

All the while, Mitat was trying to escape with little Abdullah.

ISIS did its best to keep her and other muhajarin away from local Syrians who might help them, and smugglers hesitated to help, because they faced execution if caught. Others asked exorbitant fees — as much as USD $5,000 — according to Mitat.

Eventually ISIS compelled her to marry for a third time, this time to a man who Mitat describes as a gentle soul, called Abu Abdallah Al-Afghani.

This name – given to him by ISIS — indicates he was of Afghan origin. Mitat, though, says he was Indian, and that his mother lived in Australia. She says he may have been an Australian national.

Although ISIS propaganda videos portray life in Raqqa as a believer’s paradise, Mitat says it was anything but.

It’s “like you’re dead, it’s not life,” she recalls.

She says she was “always scared, always hearing bombs, guns, shooting.” In recent months, food began running short, and power and water cuts grew longer.

Mitat had a second child, daughter Maria, with her third husband, but the more difficult the situation became, the more eager she was to flee.

She says ISIS forced Abu Abdallah to help defend the town of Tabqa, up the Euphrates river from Raqqa, from US-backed Kurdish and Arab fighters. He was killed shortly afterward.

This was Mitat’s opportunity to finally leave Raqqa.

Keeping her husband’s death a secret from neighbors and acquaintances, she sold off all her possessions and used the money to pay smugglers to get her safely to a Kurdish YPG checkpoint.

The YPG, or People’s Protection Unit, a Marxist group that has been fighting ISIS across northern Syria, handed Mitat and her two children, Abdullah, who is almost two, and 10-month-old Maria, over to intelligence officers who interrogated her and were eventually convinced she was telling the truth.

The family is now staying in a YPG safe house in northeastern Syria.

The YPG has contacted the Moroccan Embassy in Beirut about Mitat. CNN also reached out to the embassy via phone and email about her case; we did not receive a response.

Her father in Morocco hopes King Mohamed VI will see CNN’s reports about his daughter and step in to bring her home.

Mitat, though, isn’t so eager to return. She’s worried about the safety of her children.

She hopes that because the father of her first child is a British national, the family will be given British passports.

Or, she says, she hopes to move to Australia to live with the mother of her last, late husband, Abu Abdallah Al-Afghani.

But more than anything, after her odyssey from Morocco to Dubai to Afghanistan to Turkey to Syria, she’s confused.

“I don’t know where I will go,” she says. “I don’t know because my life is destroyed.”

And it all started with a click on a website.